Greenwashing is a problem for consumers and investors alike.

Greenwashing, the process conveying misleading information regarding environmental and social benefits of a given product or brand, is a long-lived phenomenon. Unfortunately, it is one key reason why consumers report difficulty making responsible purchase decisions despite a desire to do so. It is simply challenging for the average person to separate authentic product claims from greenwashed messages.

Greenwashing is not just a problem for consumers. Institutional investors, retail investors, and everyone in between face similar ambiguity as they attempt to direct capital toward investments that produce double-bottom-line or triple-bottom-line returns.

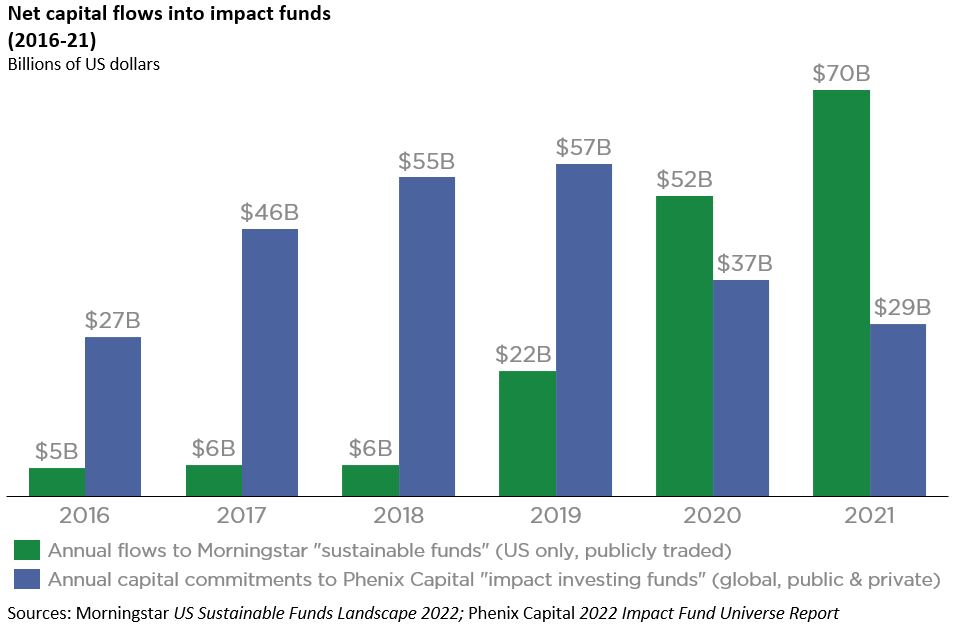

To help demonstrate the challenge, consider two different data sets that track capital flows to impact funds. The first, from Morningstar, reports that capital inflows to US publicly traded “sustainable funds” was $70B in 2021, up ~12x from just a few years ago. The second, from Amsterdam-based Phenix Capital, reports that capital commitments to “impact funds” globally, in both public and private markets, was just $29B in 2021 and down substantially from a pre-pandemic peak of $52B. Seemingly, investors increasingly seek to create positive impact with their capital, and clearly, there are widely varying methods of defining impact.

Voluntary schemes have attempted to standardize terminology, but results are mixed.

A few organizations have attempted to help standardize how investors and fund managers define “impact.” For example, some leverage the UN Sustainable Development Goals framework to categorize, measure, and track impact. Additionally, 4,902 investors, asset owners, and corporations who collectively manage $121.3 trillion of assets are signatories of the Principles for Responsible Investment, another UN-supported effort to encourage integration of ESG considerations into investment decisions. While helpful, these approaches are only voluntary, and they do not prescribe methodologies for disclosing impact policies and results.

The EU passed legislation specifically to address the financial greenwashing problem.

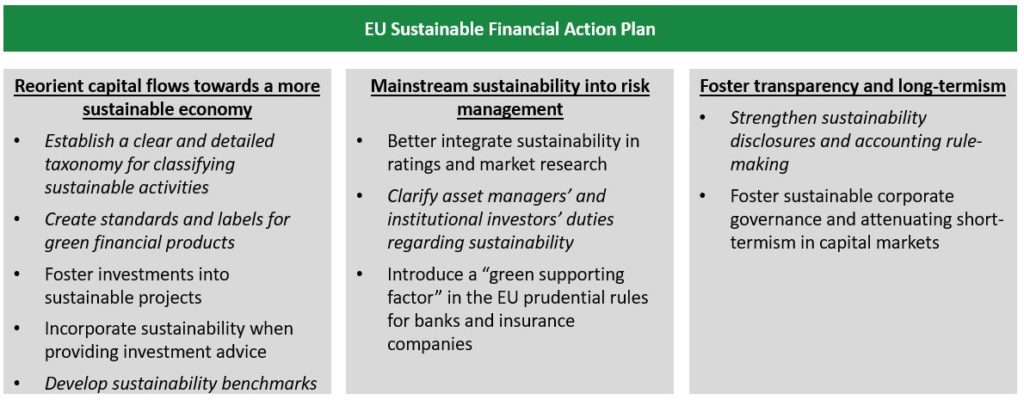

In 2018, the EU adopted the Sustainable Financial Action Plan. This action plan included 10 key actions that are divided into three categories.

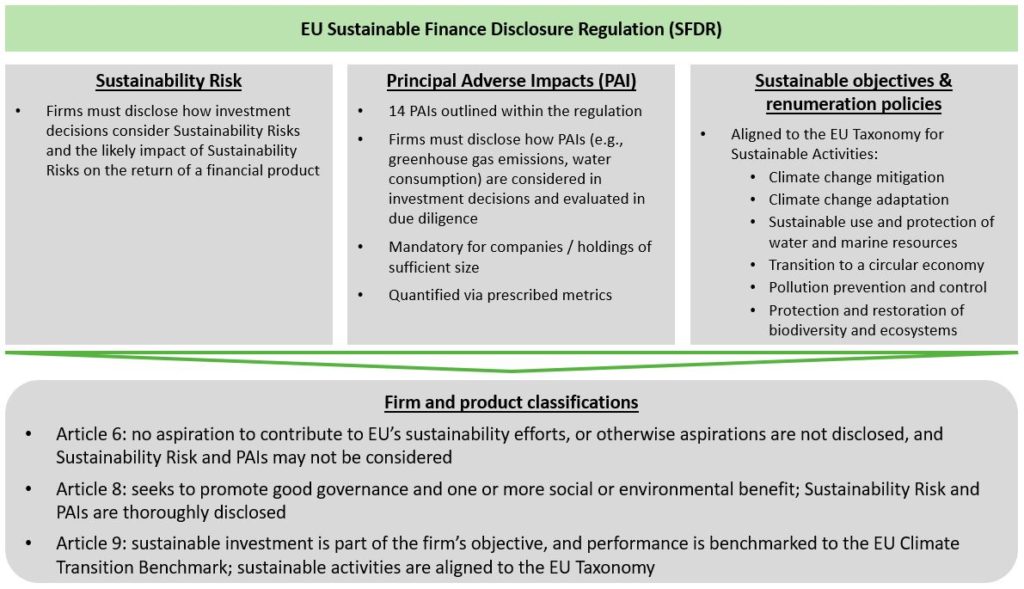

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) is an impactful law that developed out of the Sustainable Financial Action Plan. In short, SFDR seeks to improve transparency in financial markets and encourage capital flows to green investments by requiring asset managers & investment advisors to report on sustainability risk exposure, sustainability objectives, and sustainability performance in a mandatory, standardized fashion. Helpfully, the regulation also classifies firms and financial products into three categories based on their level of compliance and the degree to which they pursue sustainable investing.

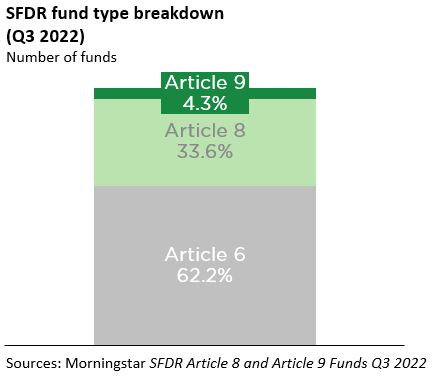

Overall, SFDR Article 9 represents a stringent standard for demonstrating commitment to sustainable investing. While we are still in the early days of the SFDR era, only 4% of EU funds currently qualify for Article 9 status.

We, Agriculture Capital, have a few takeaways.

First, SFDR represents a step in the right direction. We have long sought to demonstrate our commitment to impact to investors and the broader financial community, and we welcome a standardizing framework. We will be interested in tracking how it gets applied in practice and ultimately iterates.

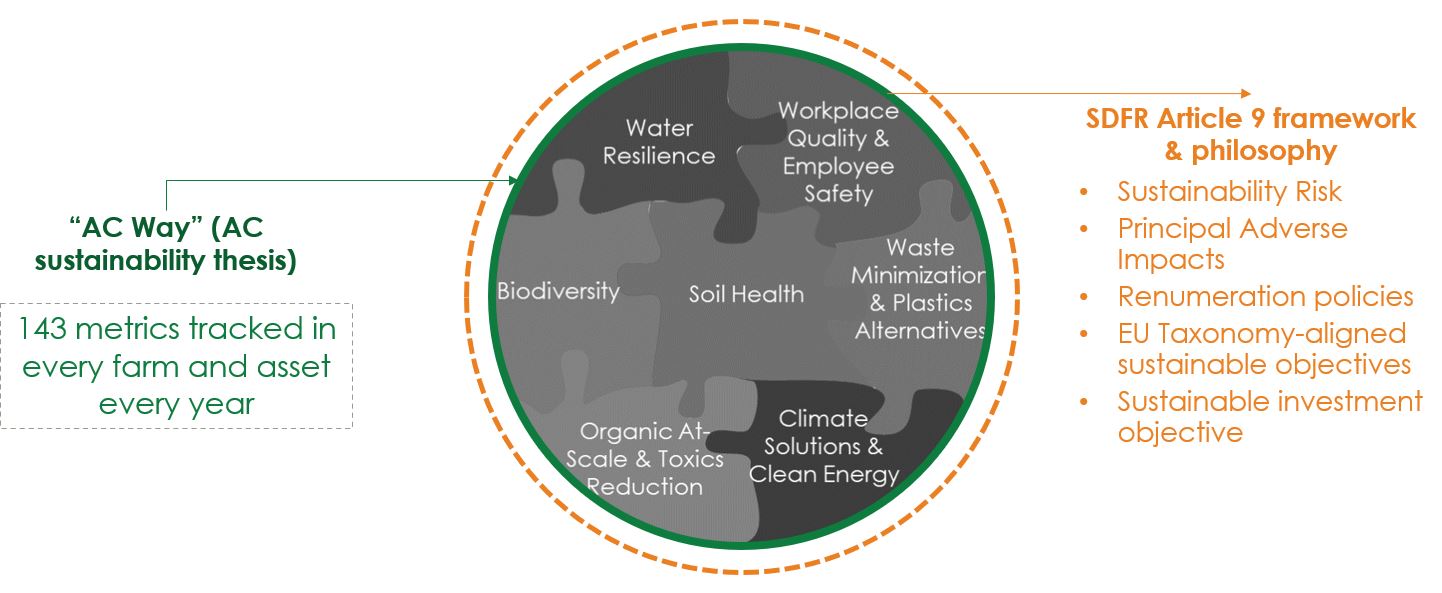

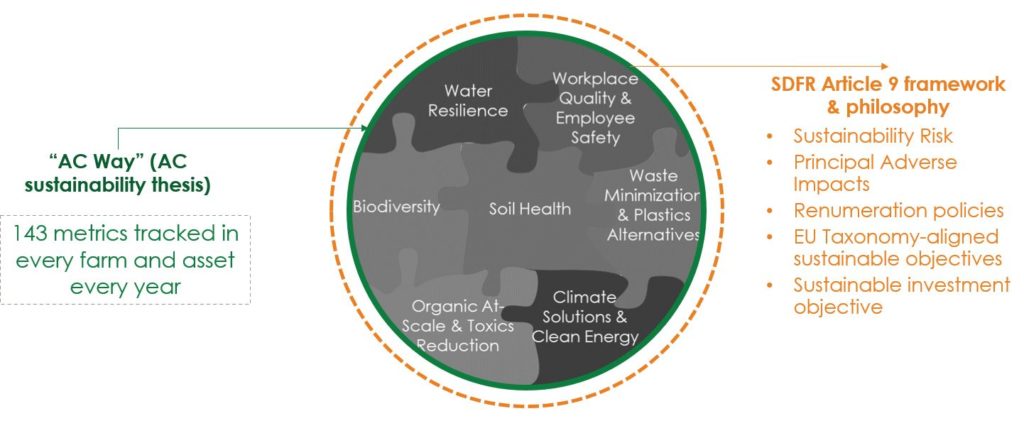

With that said, we still have a reporting journey ahead to achieve an SFDR classification that we believe reflects our regenerative, impact-driven philosophy and accomplishments. We have collected and shared progress on nearly 150 ESG metrics since we launched, but reporting to SFDR guidelines will be a new frontier for us.

Finally, we look forward to seeing how other global regions respond. In May 2022, the SEC “proposed amendments to rules and reporting forms to promote consistent, comparable, and reliable information for investors concerning funds’ and advisers’ incorporation of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors.” While the technical details of the SEC’s proposal will almost certainly differ from SFDR, it is encouraging to see broader acknowledgement of the financial greenwashing problem.