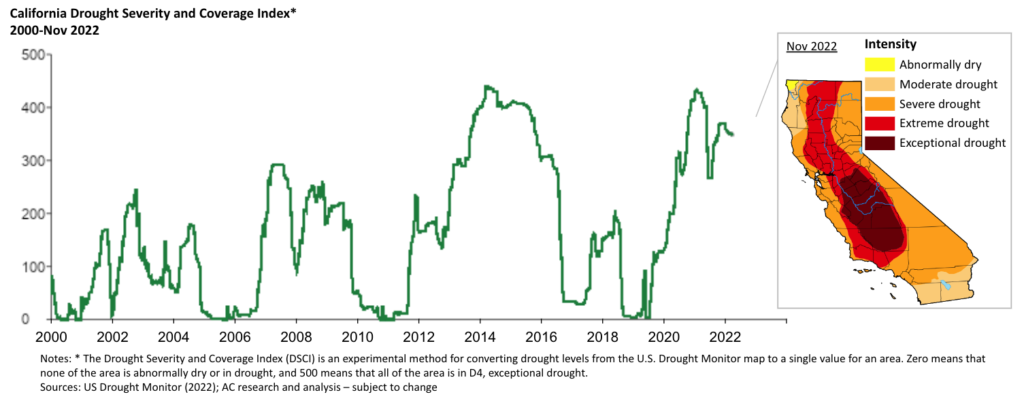

California’s record drought made headlines this year. Unfortunately, the severity of the drought is neither surprising nor transient. Experts have warned for years that drought cycles in places like the US Southwest are likely to become more frequent and more intense. The trend has become evident over the last 20 years and will likely continue or get worse. The outlook is troubling for industry, cities, and, of course, farmers who depend at least partially on surface water fed by rainfall and snowpack each year to irrigate crops.

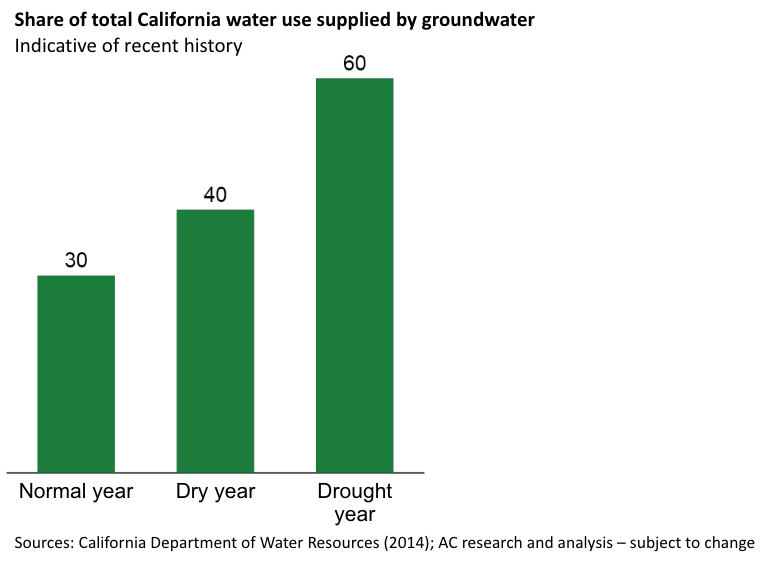

Further compounding water challenges for growers, California is in the early stages of implementing the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), which will regulate groundwater pumping for the first time in the state’s history. Until now, growers have largely made up for precipitation shortfalls by pumping water held in aquifers underground. In a normal year, groundwater supplies roughly 30% of the state’s total water needs, and that figure increases up to 60% in dry and drought years. Ultimately, the regulation will help ensure the long-term viability of California’s water resources and therefore California’s ag industry. However, in the short term, implementation will be painful.

So, what does this outlook, defined by more volatile precipitation patterns and restricted access to groundwater, mean for growers?

The answer depends on myriad factors, but to put it simply, any given parcel of California farmland is likely headed down one of two paths. One path leads to dry and difficult times while the other leads to a brighter future with higher average selling prices and accelerated asset appreciation. It gives us no pleasure to take this perspective, but we must be clear-eyed about the facts before us.

The winners in this bifurcated future will likely have two factors in their favor: reliable access to water and high profitability per acre (determined by a mix of yield per acre and crop value per unit).

Our reasoning goes as follows:

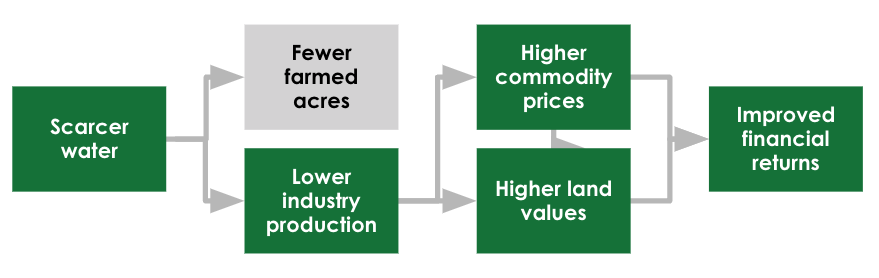

- As water becomes scarcer, the cost to farmers to procure water will likely increase, and some growers may not be able to access water at all despite their willingness to pay for it.

- Growers who cannot reliably access water or cannot absorb higher costs to procure water will have no choice but to stop production.

- As acreage goes out of production and production volumes decrease, commodity prices will increase (assuming constant and/or growing demand). This is particularly true for crops with specialized climate needs such as those grown in California’s Mediterranean climate.

- Further, with growing demand for food as well as a declining base of viable farmland, land values will likely increase at higher rates for growers who can access water and/or afford to pay more for water.

Citrus provides an insightful case study:

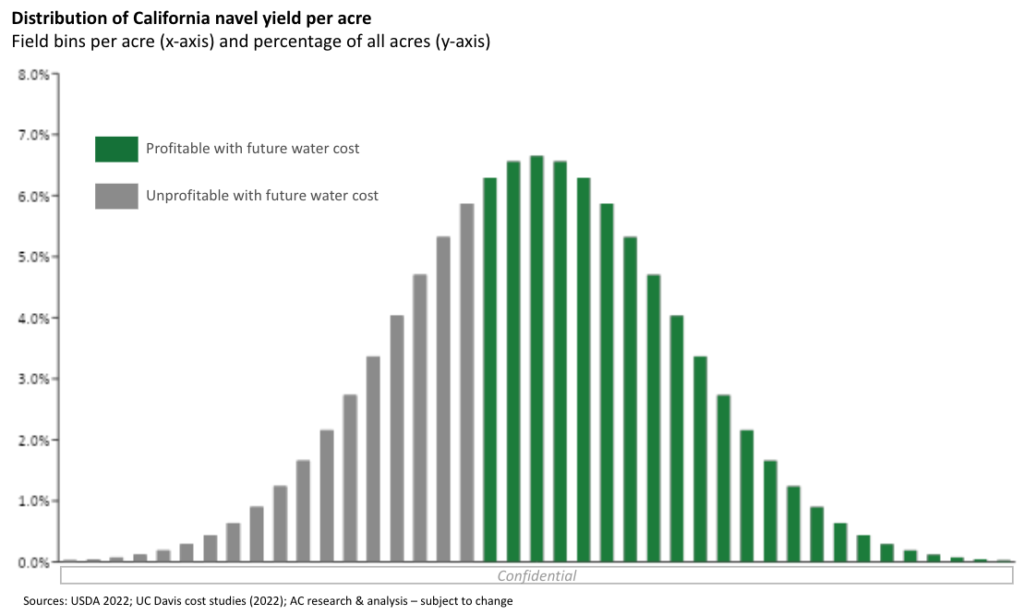

We put together a generic budget for fresh navel orange production in California assuming recent market conditions and then applied a reasonable incremental cost to procure water in a water-constrained world. Of course, our water cost forecast cannot be precise, and it may not fully enough consider potential changes to California’s water infrastructure, but our estimate allows for a directional forecast and analysis of a hypothetical situation. Using a reasonable drought condition water cost forecast, we found that ~30% of California navel acres likely do not produce sufficient yields to be profitable in California’s next drought.

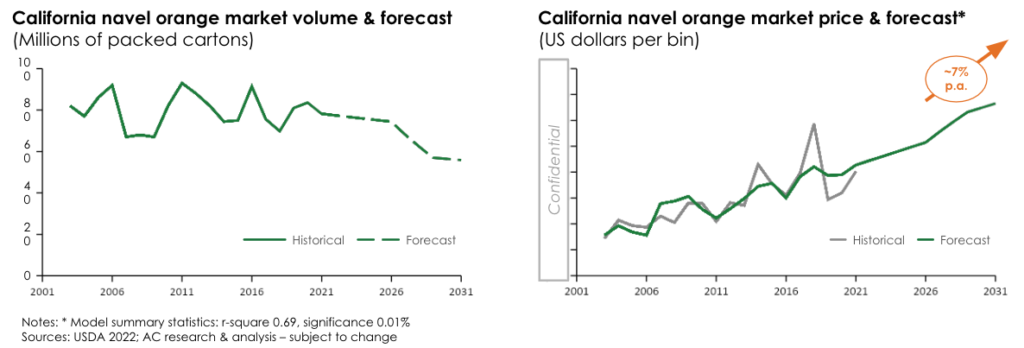

Next, we evaluated the likely impact to fresh navel prices in this scenario, assuming a substantial portion of unprofitable acres come out of production. If the prior 20 year relationship between volume and price holds, fresh navel prices will likely increase 7–8% per year throughout California’s next drought cycle (well above the recent historical average annual price growth). We cannot predict with any accuracy the timing of California’s next drought cycle, but the charts below depict a scenario where the next drought takes place from 2027–2030.

The growers who remain in production and enjoy higher selling prices will likely see profits increase despite higher costs to access water. Higher profitability per acre also means higher land value. Plus, as the demand for food, including navel oranges, increases but the base of viable farmland decreases, the value of each remaining farm will increase.

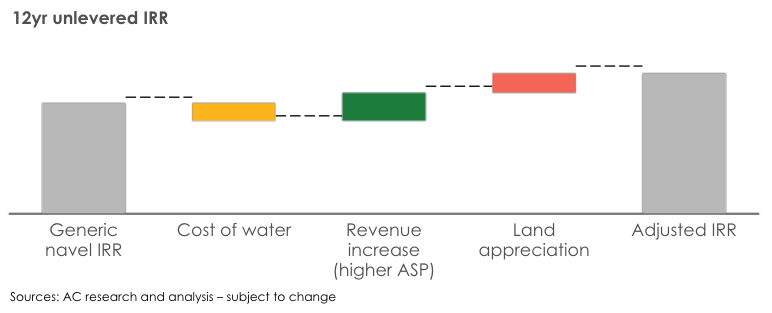

Translating the above scenario into investment outcomes yields interesting results. Once again, using a generic set of assumptions (average crop yields, average prices, average operating costs, average acquisition value, average land value appreciation, etc.), we projected the internal rate of return (IRR) for a typical navel farm investment made today and held over 12 years. Adjusting the model to consider extreme drought in 2027–2030 (again, hypothetical timing) leads to an IRR that is ~27% higher than the base case (e.g., a 10% return improves to 12.7% not 37%). Higher water costs are more than offset by higher selling prices, and the land value for this hypothetical farm also increases at a slightly higher rate than we have recently seen in the industry.

In case this is not already clear, our forecasts and analysis are subject to a seemingly endless number of variables that are difficult to predict. Further, the analysis considers a 30,000 foot view — it does not consider the particulars of any specific farm or water district. Nonetheless, the implications of our findings are clear:

- We are likely in the early stages of a divergence in fortunes for California farmland.

- Farmland investors who do not thoughtfully factor a dryer future into their financial forecasts are likely exposing themselves to serious risk.

- Farmland investors with expert understanding of California water regulations and water infrastructure likely have an advantage and are positioned to achieve attractive risk-adjusted returns.

- There are over 100 water districts in California, each with different degrees of water security and rules for grower members. The minutiae of how these entities operate layered on top of state and federal regulations and infrastructure is somewhat overwhelming but critical for projecting farmland financial performance.